I am writing about driving.

Alone.

On open roads.

Driving home, we always are.

I am writing about driving.

Alone.

On open roads.

Driving home, we always are.

“Scintillating Sentences” is what one reader calls the three-page list of sentences she underlined as she read, and then sent to me. Rather than posting them all at once, I think I will share them one at a time when the feeling hits. The one I have chosen for today makes me feel good and reminds me it can be a prayer. I remember the wonder of hearing myself say it out loud. And later, the realization that came after writing it, looking at it on the page, and knowing that was the first time in my life I felt that. I love revision. Re-vision. That great gift writing gives us to look at what we have to say again and to see it in new ways. This simple 14-word sentence is a prism through which to consider love, divinity, body, woman, and human. The scene in which it is uttered evokes the gratitude the narrator feels for what her body does for her, what it tells her, how it helps her. The body is active, the body is divine, the body is a messenger.

“Beyond brava!!! So so moving in myriad meandering meaning-filled ways,” the reader wrote at the top of the list.

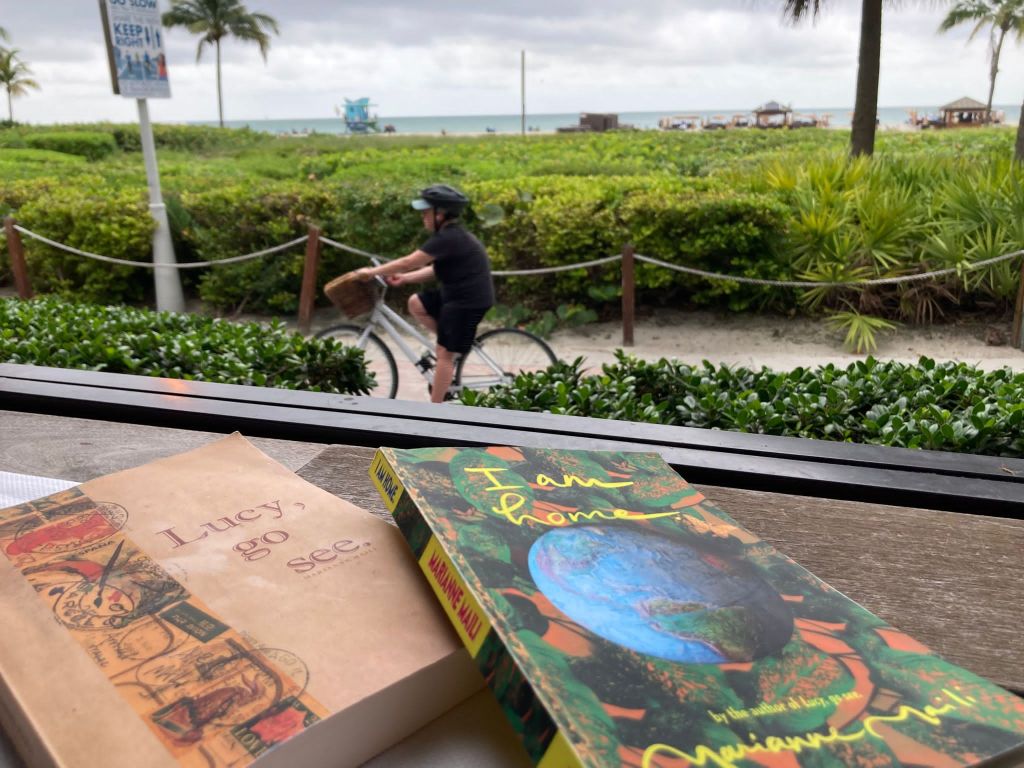

Another reader in Florida sent this image from Miami Beach. She read I am home. first and that made her want to read Lucy, go see. and tell her friends to read them both, too. “Your writing is superb. Your metaphors are really unique and lovely. I had a great time. Honestly didn’t want the books to end. I think they should be movies.”

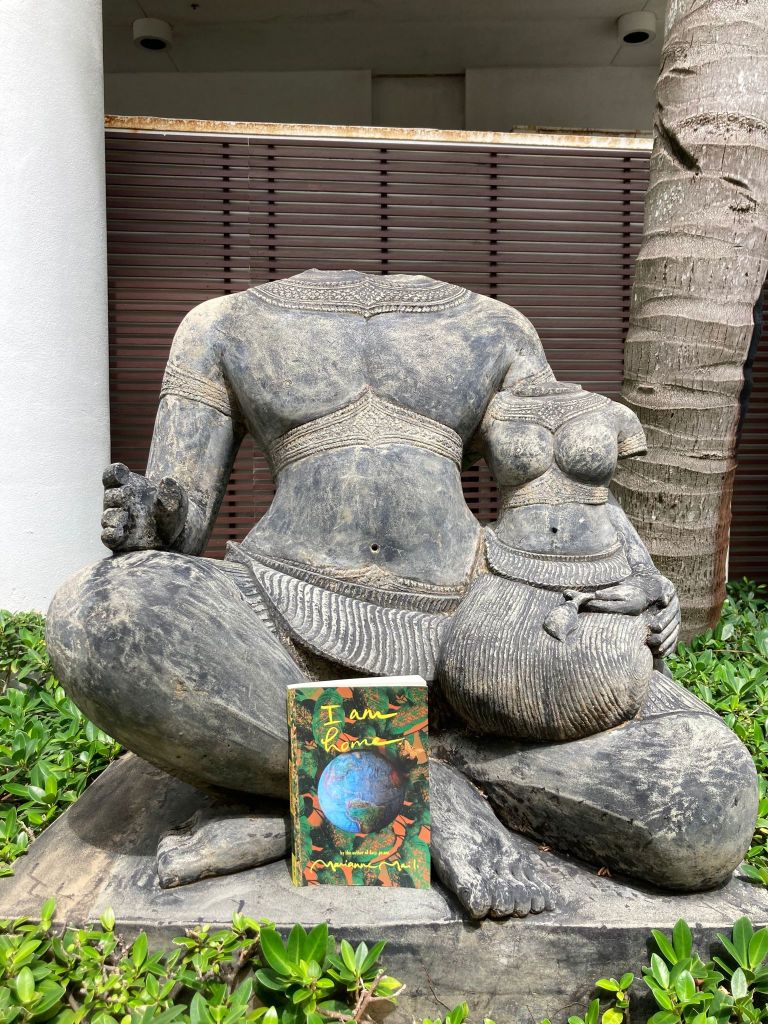

A reader sent this photo from Miami and it has left me speechless for a while. I think about motherhood when I look at it. Then I look at the breasts of what appears to be a child because of its size and what seems to be a breast-less woman holding her, and why do I think it is a woman? Because of the shape of the waist and the hips. And that breastlessness makes me think of St. Agatha. And then there is the size of the feet and I am home., a traveling book, at the feet, of this image of bigness seemingly protecting smallness. And this makes me think of another reader’s comment about how the book is about the extraordinary of the ordinary, though this image is hardly ordinary. I could probably ask someone who knows. Look at it, though, above all, headless. Headless. What happens when we lose our heads? Or when we get out of our heads and decide to live with the body and place less focus on the mind? We each have our own answers to these questions that I like to think about when I look at this image. I am home. is filled with similar questions and occasional attempts to answer them. In this way, it is also about acceptance of things as they are. It can also be a statement about being home anywhere in any way.

And when I look at it, for some reason, this sentence that many readers have liked from I am home. floats into my mind: These three bodies-the one I came from, mine, and the one I gave life to-all connect to one happiness.

“Holy Hell!” is what I said aloud when I looked at the portrait of St. Agatha holding her breasts on a platter in a chapel dedicated to her within the Royal Palace in Barcelona. It was my introduction to her so I did some research and found out how the story goes. Born in Sicily around 231 AD, she became a consecrated virgin, meaning she chose to dedicate her life to God instead of a man. Later she became a martyr. This was after Quintiamus, a supposed diplomat, was enraged by her refusal to marry him and her rejection of his advances. He ordered her breasts cut off as punishment, then imprisoned her and tortured her in many ways, while she remained true to herself. Legend has it that while she was imprisoned, she was healed and her breasts restored and the Q man, further enraged, ordered her burned alive. That is how she died in 251 AD at the age of 20.

Thinking about some of the narrator’s relationships with men in I am home. I felt a kinship with Agatha and spent time there enjoying the energy in that space near her portrait and the alcove, talking to her about courage and integrity, and telling her about experiences with refusing men almost two-thousand years later. I looked for a sign noting it was her chapel, for a sign about the painting and her life, looked for the painter’s name to no avail, and noticed on all signage of the chapel there was no mention of Agatha on the premises other than her name painted in the halo around her head. An internet search on St. Agatha’s Chapel will turn up St. Agatha’s Royal Chapel, and more. Yet, for some reason, mention of her story is omitted within this inspiring and beautiful space. I asked a woman who was touring the chapel if she knew about her and her story and after she shook her head, I told her what I knew. She then bowed before Agatha’s portrait. I wondered why there were no pews in the nave, no place to rest, other than a few low square stools off to the sides in the alcoves placed in front of televisions to watch videos about Barcelona. No mention of Agatha there, either. I slid one of the stools in front of Agatha’s portrait and under the center point of the vaulted ceiling and let all that energy charge me. I felt at home.

Leaving the theater in tears was the last thing I expected when I walked into a Barcelona theater to watch Barbie this afternoon. It was hot, and I wanted coolness, distraction, and to see what so many are talking about. I played with my sister’s hand-me-down Barbies as a girl though have no memory of great attachment other than wanting to be Malibu Barbie for a while, with a beach house and a convertible. I thought about leaving several times during the first twenty minutes of the movie, when it all seemed too much of a commercial for Mattel and Smeg, too plastic and pink for me (and I like pink), too violent, even, with the girls smashing the baby dolls and all.

Barbie and Ken’s entrance into the real world kept me in my seat and I was waiting for something to impress me and prepared with feminist eyes. And then they filled with tears–about two-thirds of the way in–when Barbie, in the back seat behind the real-world mother and daughter, realizes she crossed the border of Barbieland for the mother instead of the daughter, that it was the mother’s sadness and longing for loving and playful reconnection with her now adolescent daughter that drew Barbie to her. The tears seemed to surprise the woman sitting next to me as she saw me wiping them, then nudged the man next to her and nodded in my direction. Anyway, those tears stayed in my throat, leaking again later while the creator/mother and daughter had a conversation about what it means to be human, the elder female reassuring, encouraging, and uplifting the younger. I ached for my mother and grandmothers, all gone now, as I watched. I ached for female solidarity across generations, for my sisters and female cousins, for my aunts and nieces, all on another continent now. Barbie is a film about motherhood, the motherhood of daughters. It’s about sisterhood, impossible without motherhood. It’s about the creative power of the presence of a strong and vulnerable mother’s voice in a story. It’s about the power of birthing humanity. It contrasts the real and the ideal. It celebrates the birth of personhood. In the end, it is about everyone being at home in the world.

This is why it felt like I am home. and Lucy, go see. This is why I walked to the sea afterward, talking to my mom in heaven, and letting myself have a good cry sitting on the rocks while looking toward France, where my son lives.

A reader recently met with me and showed me all the asterisks and dog-eared pages in the book marking the places that moved her most. It was delightful to find that many of the sentences I had struggled with were in that group.

You can probably imagine my pleasure in reading this later: “I am home. is a book about searching and connecting with yourself, with loss, with love, with who you are and who you want to be, through life experiences and change. In I am home., this path is seldom straightforward, much like the author’s discourse, which gently goes back and forth in time in a way that seems almost unconscious, much like our thoughts, and our emotions. In this search for home, the author’s voice comes through as genuine and honest where self-respect and dignity are non-negotiable conditions of this search.

I thoroughly enjoyed I am home. Maili’s writing is uplifting and insightful. It’s inspirational.”

Un camino is a way and camino is also the first person present for walking in the Spanish language. So to say Camino. is to say I walk. El camino is to say the way.

Camino el camino. is to say I walk the way. What way? There are many.

Following Robert Frost’s adage about how way leads to way is a way to live. The narrator of I am home. lives like this.

I love seeing the book resting with other pilgrims in Santiago de Compostela after a lot of walking. This reader thinks “It’s a great book to accompany a pilgrimage and walking journey because it is a book about the many ways that lead us home. And the camino that leads us there is love.”

Today marks a decade since I earned a PhD from the University of Barcelona. Oh, happy day! It feels good to be here in this city of my heart and soul again to celebrate all of the life before, during, and since that moment.

Reading is sexy. Just do it. In places like this. it’s lovely to watch someone read. “El problema es cuando cojo tu libro, no puedo dejarlo,” this reader told me. In other words, “The problem is that when I pick up your book, I can’t put it down.”